The road to CITES: The tragic human cost of elephant translocations

This article was published in Africa Geographic on October 27, 2022 and authored by Gail Thomson. We publish the article in full here:

John Kayedzeka, 35, is out working in his field on the 16 September 2022, preparing it for planting later this year. His field, about 3km from Kasungu National Park, Malawi, is the main source of food for his family – a wife and two school-going children – so he works the field from the early morning hours.

Suddenly he hears shouting coming from a nearby village – perhaps people are having a loud argument? He looks up and to his surprise sees a herd of elephants moving rapidly through the bush in front of him. They are being chased back into Kasungu by the park’s rangers, who have been alerted to their presence in a nearby village. He watches with interest, but keeps a respectful distance.

What John doesn’t know is that this is not the only herd being chased back into Kasungu. Suddenly, the bush behind him erupts with the sounds of trumpeting and ground thumping. Out in the open, his only option is to run. But the elephants quickly catch up with him and knock him to the ground. He loses consciousness after the first few blows and a few seconds later his lifeless body is trampled into the ground.

Conservation and human-elephant conflict

This tragic story is not unique. Hundreds of people are killed every year by elephants and other dangerous wild animals in Africa. Yet the backstory to this incident is different to the usual human-elephant conflict occurring across the continent. Sadly, John Kayedzeka’s death was preventable.

John’s family lives in Malawi’s ‘bread basket’ or Central Region, where millions of people rely on the yields of maize and other crops for survival. Due to the high productivity of the land, this is one of the most densely populated regions in Malawi, which itself is densely populated – 20 million people living in 118,480km2.

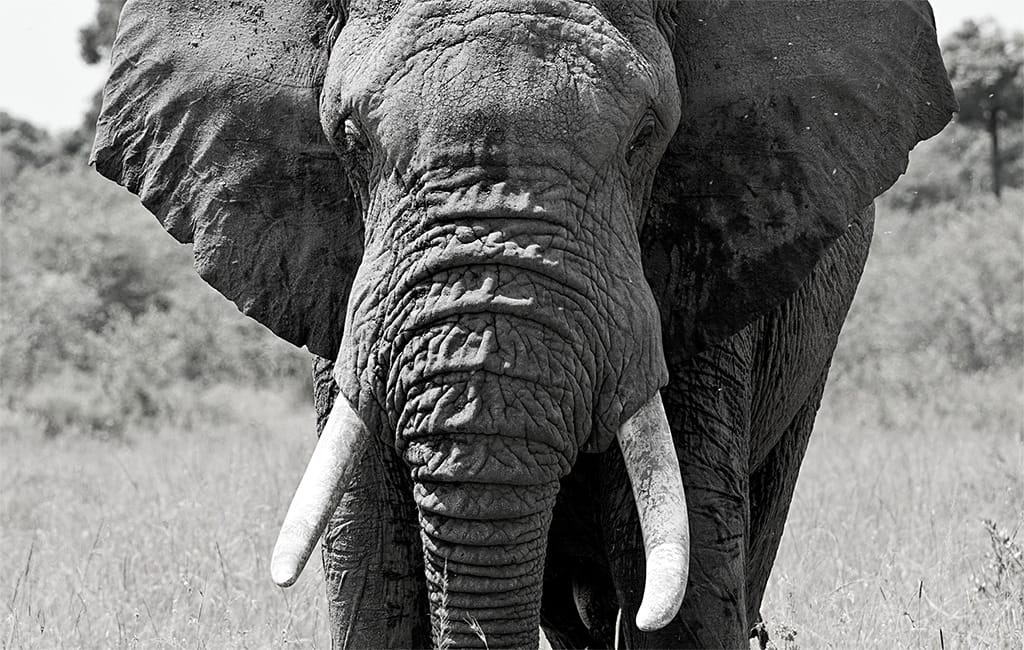

This makes setting aside land for conservation challenging. Kasungu is wedged between subsistence farmers in Malawi to the east and those in Zambia to the west. This 2,316km2 park experienced high levels of poaching in the last few decades and was therefore performing far below its conservation and tourism potential. Elephant poaching resulted in the park’s population plummeting from 1,200 elephants in the 1970s to an all-time low of 40 in 2014.

In 2015, Malawi’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) entered a partnership with the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) to address the poaching problem and improve park infrastructure. Tightening up park security during the past seven years has halted and reversed population declines of elephants and other animals. By 2022, there were an estimated 120 elephants in Kasungu. Since the elephant and other wildlife populations were still well below carrying capacity, Kasungu was identified as a potential destination for animal translocations.

Meanwhile, Liwonde National Park in Southern Malawi started experiencing the opposite problem. In the same year that IFAW started working in Kasungu, African Parks partnered with the Malawian government to manage Liwonde. By reducing poaching and reintroducing some species, African Parks restored wildlife populations in this 548km2 park. But they soon realised the need for an electric fence around the whole park, to reduce human-wildlife conflict and poaching. African Parks immediately began constructing an electric fence to keep wildlife inside the park and have since completed the 140km fencing project. In response to queries, African Parks spokesperson Carli Flemmer explains, “whilst all parks managed by African Parks in Malawi are fenced, this is not a perfect solution, and breakouts of elephants can and do still occur despite best efforts. These breakouts are a threat to human life and crops. Reinforcements and innovations in fencing technology are an ongoing effort. Some of these innovations are proving very successful.”

Consequences of a rising elephant population

Once adequately protected, elephants overpopulate relatively small, fenced reserves – making Liwonde an ideal source of elephants for other protected areas. Translocating 263 elephants from Liwonde to Kasungu, therefore, makes good conservation sense. But tripling the population of elephants in a partially fenced area has had severe consequences for some of the park’s neighbours.

Malidadi Langa, representing Kasungu Wildlife Conservation for Community Development Association (KAWICCODA), reflects on the consequences of the translocation for his community and what could have been done to prevent it: “With hindsight, maybe we [the stakeholders] should have completed the fence before translocating the elephants and other animals. Maybe we rushed the translocation. Maybe we could have better prepared for possible conflict incidents. But we cannot just look back on mistakes – we now have to do something to help widows and orphans who face an uncertain future.”

When contacted for comment, representatives of both DNPW and IFAW said they had never agreed to fence the entire eastern side of Kasungu. Patricio Ndadzela, IFAW Country Director for Malawi and Zambia, states, “IFAW has funded the construction of approximately 40km of fencing and has committed to repairing and extending a further 25km of the fence in the coming months along Kasungu’s eastern boundary in Malawi.” Following this plan, half of the park’s eastern boundary will be fenced when this project is completed, while the western (Zambian) side will remain unfenced as a corridor between Kasungu and Lukusuzi National Park in Zambia.

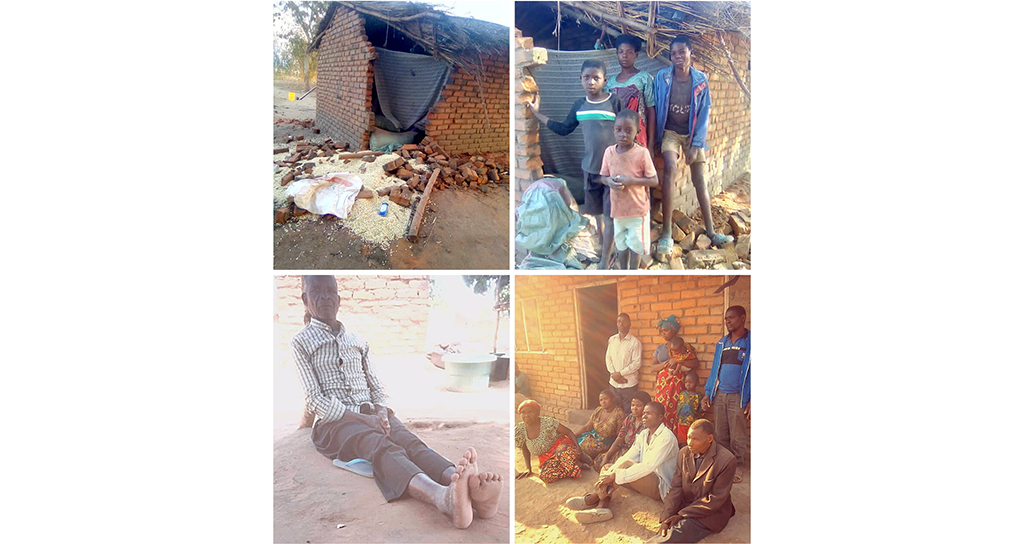

“Since there were [previously] so few elephants in Kasungu,” explains Langa, “people living on the border had experienced few crop losses before the translocation and had let their guard down in terms of vigilance against dangerous wild animals”. DNPW reported at the time that the elephants were likely attempting to trace their route back to Liwonde. Without a fence to stop the elephants, the consequences were lethal. Shortly after the first group of elephants were brought in, two people were trampled to death by bull elephants in separate incidents. One of them, Collins Chisi from Jala village in the Chisembere area, has left behind his wife and three children (14, 16 and 18 years old) whose futures are now uncertain. The other victim, Joseph Kapalamula (27) from Nason village, Mchinji district, leaves behind a wife and two young children. The elephants were subsequently euthanised by park rangers responding to the incidents.

Not long thereafter, 72-year-old Tadeyo Phiri of Mndengwe village in the Mwase area was knocked to the ground by an elephant while he was collecting thatching grass. Although he escaped alive, his injuries are severe – he cannot walk and struggles to breathe – and he cannot afford decent medical care. Phiri was therefore discharged from hospital and sent home. Five of his children are still at school, but their now-disabled father cannot work to provide for them.

On 17 August 2022, a few weeks after the translocation, elephants broke into a house where Sikwiza Mwale (33) stored several 50-kg bags of maize that she had harvested and shelled – her entire harvest for the season. After breaking down the wall of her house, the elephants ate seven of the eight bags (350 kg of maize), leaving her and her three children with too little food for the coming year.

John Kayedzeka’s death is thus just the latest of a series of incidents since elephants were translocated to Kasungu. John was in the wrong place at the wrong time and had no chance of escaping an agitated herd of elephants hurtling towards him like a freight train.

“These stories are heart-breaking,” says Langa, “but they are made even worse because none of the parties involved in moving these elephants is stepping up to help the community.” According to Malawian wildlife policies, no compensation is offered for damages or loss of life caused by wild animals. In the case of Tadeyo Phiri, the only assistance he has had is transport to the hospital provided by DNPW.

“When we ask for more help for Tadeyo Phiri, park officials just say that they don’t have money,” says Siwinda Chimowa, Chairperson of KAWICCODA, “yet clearly there was a lot of money available to bring these elephants in the first place.”

DNPW and IFAW both say that a certain level of support is provided when incidents occur. Patricio Ndadzela, IFAW’s Country Director for Malawi and Zambia, says “Malawi’s DNPW has provided one-off condolence support [to] the bereaved families. Under the National Parks and Wildlife Act of Malawi, the Government does not provide compensation either for injury or death. However, IFAW, through the traditional leadership of the Senior Chief for Kasungu district, has been exploring appropriate support for the bereaved families as is required by the cultural traditions of the district. This will ensure equitable means for their loved ones.”

Director of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW), Brighton K. Kumchedwa says, “each time there is such an accident or death, we assist with a requirement such as transport. [In cases of] death, we have assisted with the basics like food and a coffin, but not [with] compensation per se.”

Since the government cannot assist, Chimowa calls on IFAW, African Parks and their funding agencies to assist. “We understand the government policy of no compensation,” he explains, “but surely the non-state partners who funded this venture can provide some financial assistance until the fence is finished?”

In community meetings held before the translocation, DNPW promised that the communities would be protected using a combination of efforts. All of the elephant herds would be collared, ranger numbers would be increased and strategically positioned, and a helicopter would be on standby to help rangers find and herd elephants back into the park before they could harm anyone. While IFAW confirms that these measures have been put in place, Chimowa says that not enough has been done to prevent human-elephant conflict due to the translocation, insisting he has seen neither increased ranger numbers nor the helicopter.

In response to queries, DNPW’s Kumchedwa states that in “the majority of cases, the deaths or injuries have been a result of communities mobbing these elephants once they stray in the communities.” He suggested that because people were unaware of how dangerous elephants could be, “some people have been injured or killed as they try to take selfies with these animals. This is the case with the one who was severely injured as well as the last death,” says Kumchedwa. DNPW and IFAW say they are trying to rectify this situation through community awareness and education campaigns regarding elephant behaviour and human-elephant conflict.

Siwinda disputes these claims: “I met with Tadeyo Phiri after the attack – an elderly, poor man who, as far as I know, does not even own a smartphone.” He continues, “After speaking with the families and victims, I highly doubt that either he or John Kayedzeka were trying to get close to the elephants or mobbing them. In John’s case, the elephants were being chased by park rangers, not by the community.” Kumchedwa of DNPW acknowledges that in the case of John Kayedzeka, elephants were being chased back into the park by a team of rangers when he was killed.

IFAW’s involvement in Kasungu started as part of a cross-border project combating wildlife crime, implemented with funding from the US Agency for International Development (USAID) that came to an end in May this year before the elephant translocation took place.

Since that project ended, IFAW continues to provide technical support to DNPW on priority issues around Kasungu National Park. But the minimal financial assistance received for these incidents of human-elephant conflict thus far contrasts sharply with the recently tightened laws regarding wildlife crime. If someone is caught poaching in Malawi or engaging in illegal wildlife trade, they are liable for up to 30 years in prison with no option of a fine for serious offenders, or heavy fines and/or jail time for lesser offenders. While DNPW’s policy not to compensate victims of human-wildlife conflict is similar to those of other countries across Africa, John Kayedzeka’s case (and arguably the others mentioned here, too) is different. The elephants were brought into a partially fenced park, John was not harassing or trying to take photos of the elephants, and park rangers inadvertently caused the situation.

Langa further notes that there is no formal mechanism through which communities can report and have their grievances or complaints regarding human-elephant conflict addressed. According to him, the current situation requires a functional and transparent grievance redress mechanism for reporting, resolution, and swift feedback showing how the authorities deal with human-elephant conflict incidents.

While deaths and serious injuries make it into local newspapers, crop and livestock losses are likely to go unreported and uncompensated. This is particularly concerning in light of Malawi’s current food insecurity caused by a combination of climatic shocks leading to low crop yields, rising living costs due to global economic disruptions and national inflation rates. 2.6 million people are currently experiencing a food crisis, and a further 6.5 million are under food stress. These figures are expected to increase to 3.8 million in crisis and 6.7 million under stress in the coming months. In the context of rising food and living costs, the Mwale family’s situation is desperate after losing nearly 90% of their harvest to elephants.

Despite their understandable frustration, the community is looking for solutions rather than someone to blame for the current situation. KAWICCODA is making a few reasonable requests of those involved in the translocation and current management of Kasungu National Park (both state and non-state actors):

- Prioritise fence construction on the eastern side of the park and set a deadline for completing the entire 125km fence line;

- Set up a platform where communities can report their losses resulting from wildlife;

- Provide financial assistance to all of the families who have suffered thus far due to the elephant translocation, and commit to providing such assistance until the fence is complete; and

- In cases where elephants get out of the park, alert people to the problem before attempting to chase the elephants back into the park.

Bringing elephants and other wildlife to Kasungu is not a bad idea from a conservation and tourism perspective. DNPW has promised to share tourism revenue with neighbouring communities, and KAWICCODA reports that they have already received small amounts of money from the park. Consequently, the people living next to Kasungu are not against reinvigorating the park through wildlife translocations, but human lives are too high a price to pay for future tourism revenues. Hopefully, this call for help will result in practical solutions to prevent further loss of life.